Designers know that low cognitive load is important for accessibility, and that the average player isn’t memorizing your 300+ page rulebook. So why do we keep inundating games with rules like this…

Seems like a silly thing to complain about (we’ll get to more offensive examples, trust me,) until you consider that D&D is wrapped with 50 years of culture and convention. For many experienced players, Dodge, Ready, Disengage, Hide, Grappling, Shoving, and Opportunity Attacks might feel second nature…

…but your game is unlikely to have the same luxury.

I refer to the rules above as “floating rules” or “mechanics in isolation,” not because they don’t interact with other parts of the game, but because it’s not under the player’s direct purview. It just lives somewhere in the core rulebook, and you’ll need to remember it.

If you’re making anything other than a rules-light system, it’s likely the players are going to have a lot to remember. If you’re building a D&D-like experience, you can often lean on the conventions already set by it and similarly long-lived TTRPGs.

However, you start running into issues when branching into less familiar territory.

Balancing cognitive load (how much information a player needs to retain to play the game) is a huge portion of a designer’s job. Mechanics should be elegantly designed, easy to remember, and natural to interact with. That’s the ideal, at least.

The more specific, absurd, or infrequent a rule is, the more it will be forgotten, the less it will be used, and the slower the game will become when it does come up.

To drill the point home…

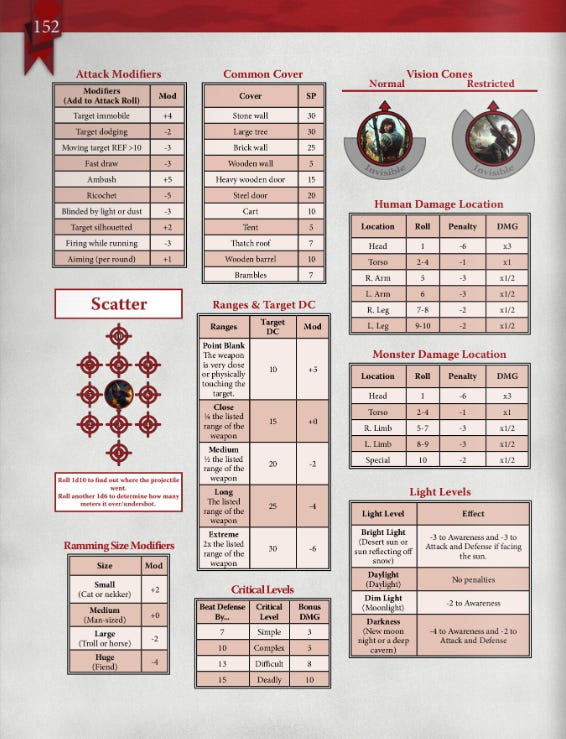

The Witcher (2018) TTRPG is painfully inaccessible. You simply cannot play the game without thumbing through the rulebook during play — there are tables for almost everything. This causes the game to be incredibly slow moving, and rejects all but the most dedicated players.

It’s the definition of inelegant design.

Despite the above page being a sort of “quick reference” of many of the important combat tables — it doesn’t encapsulate a lot of the combat gameplay, which you will still need to look up or memorize the rules for. Much like the D&D example earlier, I consider all of these tables and mechanics as isolated or floating.

If your goal is accessibility (which may not have been a goal for Witcher,) your design should keep references to the book as minimal as possible, which also means keeping your design as clean and memorable as possible.

That said, let’s look at some very simple steps toward more accessible design.

Consider the information players have ownership of.

The information on a character sheet is almost always in focus. It’s easily accessible, it’s been written it down (which is helpful for retention,) and it’s the most tangible, physical connection a player has to the game.

In other words, they take “ownership” of that information.

Character sheets can guide the game.

You can package references to important rules on a character sheet; and the design of a character sheet itself often points toward how a game is played, by emphasizing which elements are important, and grouping information in a way that reminds the player of what they can do.

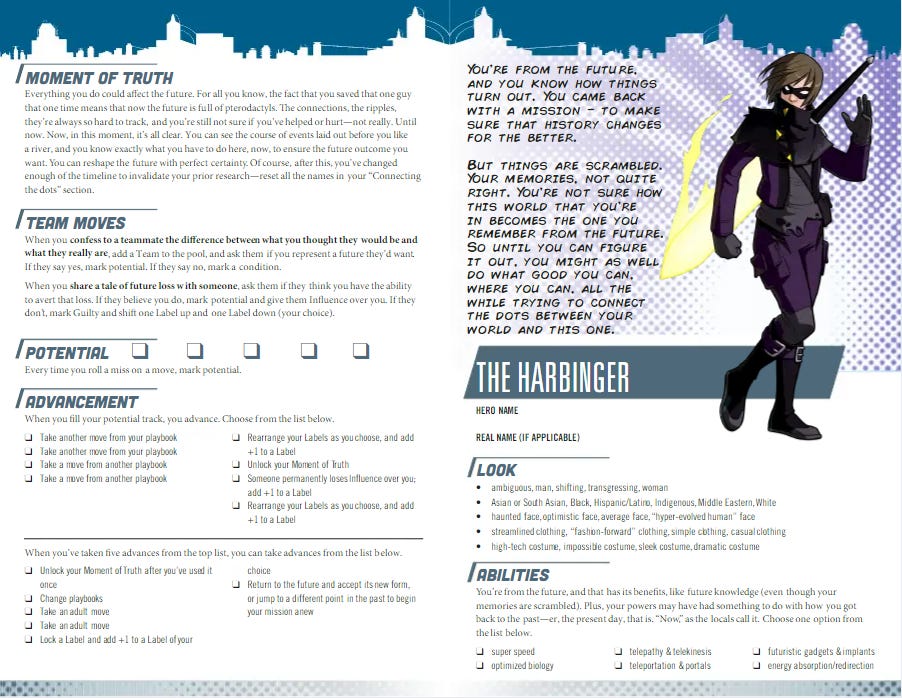

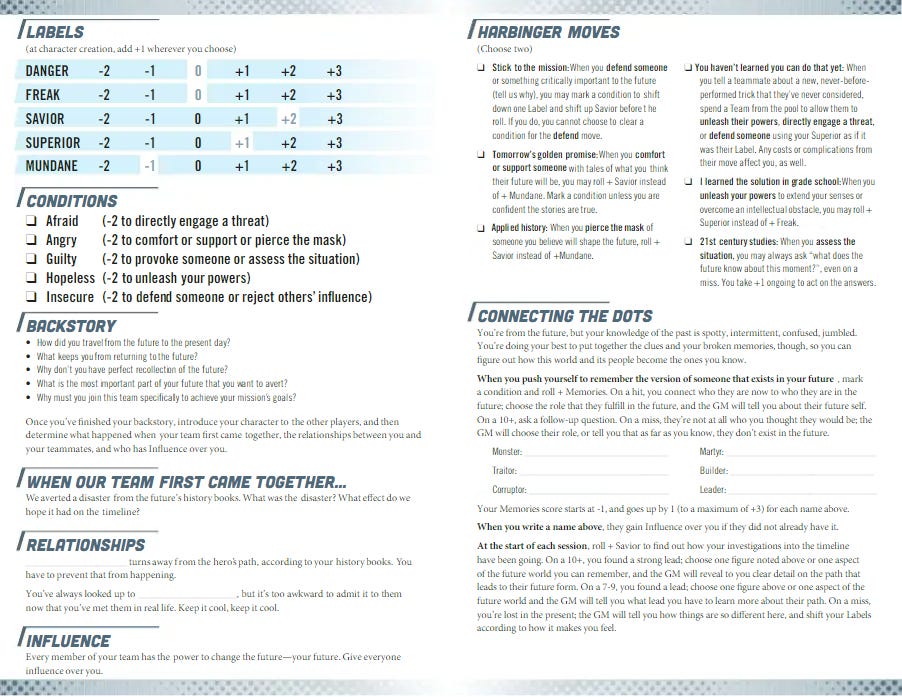

Powered by the Apocalypse (PBtA) games like Masks (shown below) call their character sheets “Playbooks” that are verbose, and help you play the game — instead of just being a container for letters and numbers.

Classes are a great way to package information.

If my class gets the “Dodge Action” at level 1, and then describes what that does — that’s way different than if it were a free floating rule that affected everyone, but no one could reference without the book.

One is written on the character sheet when you level, the other isn’t.

D&D’s Monk and Rogue classes do this to some degree by modifying the Dodge and Hide rules. Instead of an Action, the class allows you attempt them as a Bonus Action. This means that the players of those classes have an immediate investment in knowing those floating rules, and they become part of the character.

It’s a great way to make sure the rules allocate important space in memory.

Peripherals are helpful, as well.

I wouldn’t expect players to carry around an entire book with them (or enough handouts that you may as well,) but there’s a reason why decks of spell cards exist. They’re accessible, fun, and require no additional bandwidth from the player to use.

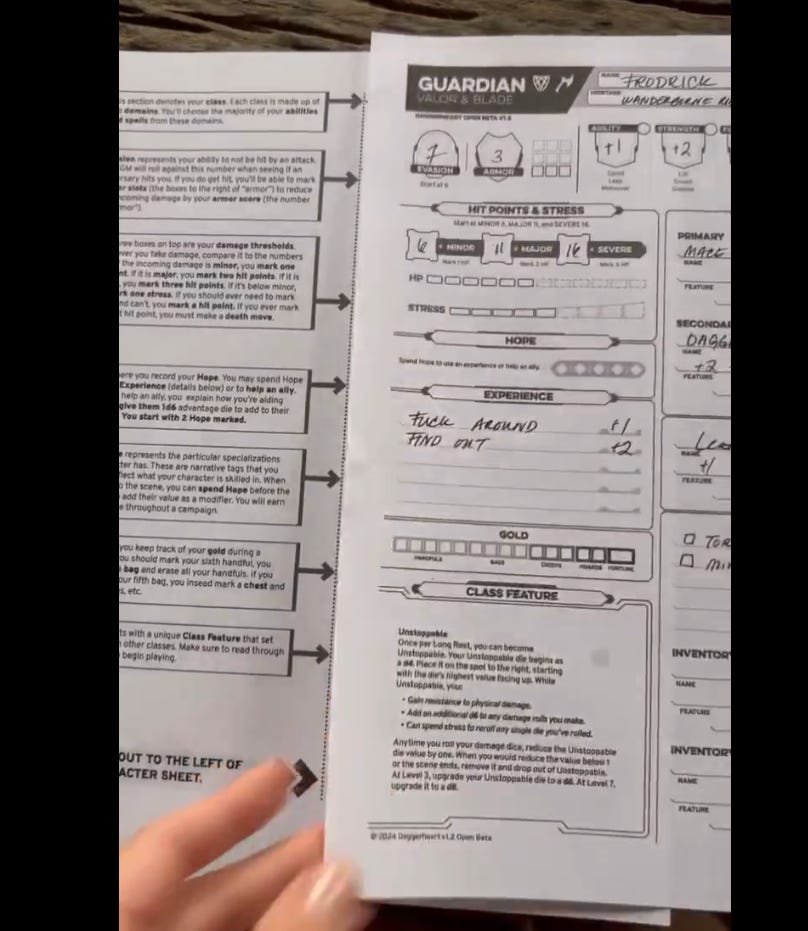

Part of your character sheet can always be devoted to important rules, like the Masks example above. Daggerheart does a good job of this as well, using a separate page (called a “sidecar”) that slides beneath the main character sheet, and describes rules interactions with various aspects of the character sheet.

Clean up your design.

I could do a whole blog post on making designs more elegant, and… I probably will, but until then let me rapid-fire some additional points to consider when dealing with cognitive load and floating mechanics.

If a mechanic doesn’t interact with at least three important systems, delete it.

Keywords and conditions are cool, but they aren’t a substitute for natural language. Find a balance of both.

Focus less on individual rules and more on how/why a player is interacting with them.

Optional rules shouldn’t exist unless they’ll be used very, very often. That’s what supplemental material is for.

Thanks very much folks.

-Wrel